This post continues the series, “The Beast of Revelation Was Zealot-Led Israel.” The introduction and outline to this series can be seen here.

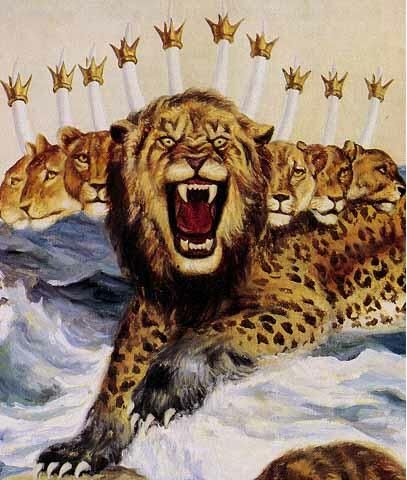

In the previous post we looked at Revelation 13:1-2. We considered how the beast in John’s day had Babylonian, Persian, and Greek traits. We also looked at how the Zealots and Jewish leaders in the first century followed the same pattern as Satan, who gave his power, throne, and authority to the beast. They frequently accused others, especially the brethren, just like Satan did (Rev. 12:10).

This post will examine Revelation 13:3 and the wounded head, and it includes an extensive overview of the Zealot movement and 12 key leaders of that movement. This is a long post, but even if you disagree that Zealot-led Israel was the beast of Revelation, I believe you’ll find it to be resourceful and informative.

Revelation 13:3

“I saw one of his heads as if it had been mortally wounded, and his deadly wound was healed. And all the world marveled and followed the beast.”

The seven heads of the beast are first mentioned in Revelation 13:1, and are later spoken of in more detail in Revelation 17:9-11. Here in verse 3, John tells his readers that one of those heads would be mortally wounded. Although I would prefer to wait until we reach Revelation 17 to discuss the seven heads, it’s necessary to do so at this point in order to try to identify the wounded head. It’s in Revelation 17 that John told his readers that:

- five of the seven heads had already fallen;

- one was;

- one hadn’t come yet, and he would only “continue a short time”;

- “the beast that was, and is not, is himself also the eighth, and is of the seven, and is going to perdition.”

An Overview of the Zealots/Sicarii

In this post I will propose that the seven heads were seven leaders of the Zealot movement, which Josephus also called “the Fourth Philosophy.” While examining an overview of the movement and its key figureheads, we will consider who the seven heads of the beast were. My proposal is that they all belonged to the family dynasty of Hezekiah (mid-1st century BC) which dominated the Zealot movement for 120 years. This post will discuss the following Zealot/Sicarii leaders (members of Hezekiah’s family dynasty are in bold font):

1. Hezekiah (mid-1st century BC)

2. Judas the Galilean (early 1st century AD; son of Hezekiah)

3. Zadok the Pharisee (early 1st century AD: worked with Judas)

4. Jacob (mid-1st century AD; son of Judas)

5. Simon (mid-1st century AD; son of Judas)

6. Jair (mid-1st century AD; son of Judas)

7. Eleazar ben Ananias (AD 66)

8. Eleazar ben Jair (AD 66-73)

9. Menahem (AD 66; son or grandson of Judas)

10. Eleazar ben Simon (AD 66-70)

11. John Levi of Gischala (AD 66-70)

12. Simon Bar Giora (AD 66-70; uncle of Eleazar ben Simon)

Ray Vander Laan is an author and a teacher who “has been actively involved in studying and teaching Jewish culture” since 1976. In his book, “Life and Ministry of the Messiah,” he includes the following outline of the Zealot movement’s key leadership (p. 130). Even though Eleazar ben Simon, John Levi of Gischala, and Simon Bar Giora held positions of great power in Jerusalem during the Jewish-Roman War, Ray’s outline of the Zealot leadership is limited to the family dynasty of Hezekiah:

Here Ray lists seven Zealots, all within the family of Hezekiah, extending from 47 BC to AD 73, a period of 120 years:

- Hezekiah

2. Judah (son of Hezekiah)

3. Jacob (son of Judah)

4. Simeon (son of Judah)

5. Yair (son of Judah)

6. Eleazar ben Yair

7. Menahem

In 1961 Martin Hengel, a German historian and professor, published a book titled, “The Zealots: Investigations into the Jewish Freedom Movement in the Period from Herod I until 70 A.D.” Hengel listed these same seven Zealots on page 332 of his book, where he outlined “the dynasty that began with Hezekiah the ‘robber captain’”:

The Zealot movement is defined by Wikipedia as follows:

“The Zealots were originally a political movement in 1st century Second Temple Judaism which sought to incite the people of Judaea Province to rebel against the Roman Empire and expel it from the Holy Land by force of arms, most notably during the First Jewish–Roman War (66-70). Zealotry was the term used by Josephus for a ‘fourth sect’ during this period.”

Rabbi Joseph Telushkin (a Jewish scholar, lecturer, author, and senior associate of the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership) gives the following summary of the political undercurrents which fueled the Zealots’ opposition toward Rome. This summary is adapted from his 1991 book, “Jewish Literacy,” and is archived at the Jewish Virtual Library:

No one could argue with the Jews for wanting to throw off Roman rule. Since the Romans had first occupied Israel in 63 B.C.E., their rule had grown more and more onerous. From almost the beginning of the Common Era, Judea was ruled by Roman procurators, whose chief responsibility was to collect and deliver an annual tax to the empire… Equally infuriating to the Judeans, Rome took over the appointment of the High Priest… As a result, the High Priests, who represented the Jews before God on their most sacred occasions, increasingly came from the ranks of Jews who collaborated with Rome…

The Jews’ anti-Roman feelings were seriously exacerbated during the reign of the half-crazed emperor Caligula, who in the year [AD] 39 declared himself to be a deity and ordered his statue to be set up at every temple in the Roman Empire. The Jews, alone in the empire, refused the command… Only the emperor’s sudden, violent death saved the Jews from wholesale massacre…

In the decades after Caligula’s death, Jews found their religion subject to periodic gross indignities, Roman soldiers exposing themselves in the Temple on one occasion, and burning a Torah scroll on another…

In the year 66, Florus, the last Roman procurator, stole vast quantities of silver from the Temple. The outraged Jewish masses rioted and wiped out the small Roman garrison stationed in Jerusalem. Cestius Gallus, the Roman ruler in neighboring Syria, sent in a larger force of soldiers. But the Jewish insurgents routed them as well. This was a heartening victory that had a terrible consequence: Many Jews suddenly became convinced that they could defeat Rome, and the Zealots’ ranks grew geometrically…

When the Romans returned, they had 60,000 heavily armed and highly professional troops. They launched their first attack against the Jewish state’s most radicalized area, the Galilee in the north [in 67 AD]. The Romans vanquished the Galilee, and an estimated 100,000 Jews were killed or sold into slavery… The highly embittered refugees who succeeded in escaping the Galilean massacres fled to the last major Jewish stronghold—Jerusalem. There, they killed anyone in the Jewish leadership who was not as radical as they. Thus, all the more moderate Jewish leaders who headed the Jewish government at the revolt’s beginning in 66 were dead by 68—and not one died at the hands of a Roman. All were killed by fellow Jews… The scene was now set for the revolt’s final catastrophe.

Zealots and Sicarii

The Sicarii were famous for hiding their daggers in their cloaks and using them to secretly target their enemies during the festivals (Antiquities 20.8.10). Some sources make a sharp distinction between the Zealots and the Sicarii, while others do not. It seems fair to say that the Sicarii were part of the Zealot movement, but not all Zealots were Sicarii. Thus, “Zealot” was an umbrella term for the revolutionaries who rebelled against Rome.

Some sources say that those who belonged to the family dynasty of Hezekiah were all Sicarii. Wikipedia designates the Sicarii as “a splinter group of the Jewish Zealots.” The Sicarii are mentioned in Acts 21:38, where Paul was asked if he was the Egyptian who had led 4000 assassins (or “dagger-bearers”) into the wilderness. According to Encyclopedia Judaica,

“The name [‘Sicarii’] derived from the Latin word sica, ‘curved dagger’; in Roman usage, sicarii, i.e., those armed with such weapons, was a synonym for bandits. According to Josephus, the Jewish Sicarii used short daggers, μικρἁ Ξιφίδια (mikra ziphidia), concealed in their clothing, to murder their victims, usually at religious festivals (Wars, 2:254–5, 425; Ant., 20:186–7). The fact that Josephus employs the Latin sicarii, transliterated into Greek as σικαριοι (sikarioi) suggests that he adopted a term used by the Roman occupation forces; his own (Greek) word for ‘bandit,’ which he more generally uses to describe the Jewish resistance fighters, is λησταί (lestai).”

“Sicarii.” Encyclopaedia Judaica. Encyclopedia.com. 4 Mar. 2017.

Photo Source: Pinterest (Sicarii Dagger)

A classic article by the Israeli historian, Menahem Stern (1925-1989), “Zealots and Sicarii,” proposed a distinction between the Sicarii and the Zealots in terms of their loyalty:

“The Sicarii continued to be loyal to the dynasty of Judah the Galilean, their last leaders being Menahem and Eleazar b. Jair, who were scions of that house; in contrast the Zealots showed no particular loyalty to any house or dynasty.”

This article also pointed out that a “revolutionary government” was set up in Jerusalem near the beginning of the Jewish-Roman War (AD 66-73), but lasted for only about six months. This was the same temporary government that, just after the Jews defeated Cestius Gallus in November AD 66, appointed 10 Jewish generals to lead the inevitable war with Rome (Wars 2.20.3-4):

“Just before the war, ‘a kind of enmity and factionalism broke out among the high priests and leaders of the Jerusalem populace’ who joined hands with ‘the boldest revolutionaries’ to carry out their high-level power feuds (Ant. 20:180, cf. Pes. 57a)… And significantly, the first revolutionary government formed in Jerusalem in 66 C.E. and lasting about six months was composed of high priests, noble priests, and lay nobility: the roster of noble rebels is long. These rebellious aristocrats joined the struggle for a variety of motives, including desire to protect their local power and influence, a feeling of genuine outrage at abuses by the Roman procurators, and infection by the messianic fervor and eschatological hopes pervading Judea before the war.”

This revolutionary government soon gave way to the Zealot leaders who seized control of Jerusalem over the following 3.5 years: Eleazar ben Simon, John Levi of Gischala, and Simon Bar Giora. Momentarily we’ll look at these three characters, but let’s start at the beginning and look at 12 Zealot/Sicarii leaders, beginning with Hezekiah.

Hezekiah

On page 313 of his book, “The Zealots,” Martin Hengel explained why a Jewish hero by the name of Hezekiah should be considered the first head of the Zealot movement:

“A historical outline of the Jewish freedom movement between the reign of Herod I and 70 A.D. has to begin at the point where Josephus speaks for the first time about Jewish ‘robbers,’ which is the most general term that he uses to include all the groups opposing foreign rule. We come across these ‘robbers’ quite abruptly in connection with the sending of the young Herod to Galilee as commander-in-chief.”

Hengel then cited the first occasion where Josephus spoke of these “robbers” in his works. In 46 BC Herod captured “the robber captain Hezekiah,” took him prisoner, and “had him put to death with many of his robbers” (see Josephus, Antiquities 14.9.2-3). In Wars 1.10.5, Josephus says that Hezekiah had “a great band of men.” It may be noteworthy that Josephus calls Hezekiah “the head,” the same term that John used in Revelation 13:1, 3; 17:3, 7, 9-11:

“Now Herod was an active man, and soon found proper materials for his active spirit to work upon. As therefore he found that Hezekias, the head of the robbers, ran over the neighboring parts of Syria with a great band of men, he caught him and slew him, and many more of the robbers with him; which exploit was chiefly grateful to the Syrians…”

Kaufmann Kohler, PHD, Rabbi Emeritus of Temple Beth-El (New York) and President of Hebrew Union College (Cincinnati, Ohio), also agrees that the Zealot movement began in the time of Herod the Great and Hezekiah. He says that the Zealots were an “aggressive and fanatical war party from the time of Herod until the fall of Jerusalem and Masada. The members of this party bore also the name Sicarii… The reign of the Idumean Herod gave the impetus for the organization of the Zealots as a political party.” (Jewish Encyclopedia: Zealots).

Menahem Stern also saw Hezekiah as the founder of a movement which eventually spread throughout the entire Jewish Diaspora:

“Hezekiah and his son were the founders of a dynasty of leaders of an extremist freedom movement, a dynasty which it is possible to trace until the fall of Masada… They, the proponents of the Fourth Philosophy, were the first to raise the standard of revolt…and preached rebellion throughout the length and breadth of the Diaspora.”

1st Century Jewish Diaspora (Jewish Virtual Library)

The following description of “Hezekiah (The Zealot)” in The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) reveals that his rebellion was in response to the actions of Pompey the Great, who conquered Judea in 63 BC. It also reveals that Hezekiah was beheaded:

“He fought for Jewish freedom and the supremacy of the Jewish law at the time when Herod was governor of Galilee (47 B.C.). When King Aristobulus, taken prisoner by the Romans, had been poisoned by the followers of Pompey, Hezekiah (‘Ezekias’ in Josephus, ‘Ant.’ xiv. 9, §§ 2 et seq) gathered together the remnants of that king’s army in the mountains of Galilee and carried on a successful guerrilla war against the Romans and Syrians, while awaiting the opportunity for a general uprising against Rome. The pious men of the country looked upon him as the avenger of their honor and liberty. Antipater, the governor of the country, and his sons, however, who were Rome’s agents in Palestine, viewed this patriotic band differently. In order to curry favor with the Romans, Herod, unauthorized by the king Hyrcanus, advanced against Hezekiah, took him prisoner, and beheaded him, without the formality of a trial; and he also slew many of his followers. This deed excited the indignation of all the patriots. Hezekiah and his band were enrolled among the martyrs of the nation.”

Because many of the Jews were angry with Herod, an effort was made by the Sanhedrin to bring him to trial over what he had done to Hezekiah.

Judas the Galilean (Hezekiah’s son) and Zadok

Over the next half century, more robbers followed in Hezekiah’s trail throughout Galilee and Judea, but it was his son, Judas the Galilean, who took the movement to the next level. Kaufmann Kohler said this about the period after which Herod the Great repeatedly crushed the rebellions of Hezekiah and those who rose up after him:

“The spirit of this Zealot movement, however, was not crushed. No sooner had Herod died (4 C.E.) then the people cried out for revenge (“Ant.” xvii. 9, § 1) and gave Archelaus no peace. Judea was full of robber bands, says Josephus (l.c. 10, § 8), the leaders of which each desired to be a king. It was then that Judas, the son of Hezekiah, the above-mentioned robber-captain, organized his forces for revolt, first, it seems, against the Herodian dynasty, and then, when Quirinus introduced the census, against submission to the rule of Rome and its taxation.”

According to Josephus, “the Fourth Philosophy” was founded by Judas of Galilee. Martin Hengel, however, didn’t believe that Josephus provided evidence that Judas, rather than his father, was the founder. He pointed out that Josephus merely noted a “great increase” of robbers because of the exploits and teachings of Judas: “[All] that [Josephus] says of the founding of the fourth sect of philosophy by Judas the Galilean is that it led to a great increase in the scourge of robbers” (Hengel, p. 41).

Like the “robbers” before him, Judas seemed to concentrate his activities around Sepphoris (Antiquities 14.15.4 and Antiquities 17.10.5), the capital of Galilee which was not far from Nazareth. Here’s how Josephus described “the Fourth Philosophy” of the Zealots, and how Judas of Galilee laid the groundwork for this movement near the time of Jesus’ birth (Antiquities 18.1.1-6):

“1. NOW Cyrenius, a Roman senator… came himself into Judea, which was now added to the province of Syria, to take an account of their substance, and to dispose of Archelaus’s money; but the Jews, although at the beginning they took the report of a taxation heinously, yet did they leave off any further opposition to it, by the persuasion of Joazar, who was the son of Beethus, and high priest; so they, being over-persuaded by Joazar’s words, gave an account of their estates, without any dispute about it. Yet was there one Judas, a Gaulonite, of a city whose name was Gamala, who, taking with him Sadduc [Zadok], a Pharisee, became zealous to draw them to a revolt, who both said that this taxation was no better than an introduction to slavery, and exhorted the nation to assert their liberty;

…so men received what they said with pleasure, and this bold attempt proceeded to a great height. All sorts of misfortunes also sprang from these men, and the nation was infected with this doctrine to an incredible degree; one violent war came upon us after another, and we lost our friends which used to alleviate our pains; there were also very great robberies and murder of our principal men. This was done in pretense indeed for the public welfare, but in reality for the hopes of gain to themselves; whence arose seditions, and from them murders of men, which sometimes fell on those of their own people, (by the madness of these men towards one another, while their desire was that none of the adverse party might be left,) and sometimes on their enemies; a famine also coming upon us, reduced us to the last degree of despair, as did also the taking and demolishing of cities; nay, the sedition at last increased so high, that the very temple of God was burnt down by their enemies’ fire.

Such were the consequences of this, that the customs of our fathers were altered, and such a change was made, as added a mighty weight toward bringing all to destruction, which these men occasioned by their thus conspiring together; for Judas and Sadduc, who excited a fourth philosophic sect among us, and had a great many followers therein, filled our civil government with tumults at present, and laid the foundations of our future miseries, by this system of philosophy, which we were before unacquainted withal, concerning which I will discourse a little, and this the rather because the infection which spread thence among the younger sort, who were zealous for it, brought the public to destruction.

2. The Jews had for a great while had three sects of philosophy peculiar to themselves; the sect of the Essenes, and the sect of the Sadducees, and the third sort of opinions was that of those called Pharisees; of which sects, although I have already spoken in the second book of the Jewish War, yet will I a little touch upon them now…

6. But of the fourth sect of Jewish philosophy, Judas the Galilean was the author. These men agree in all other things with the Pharisaic notions; but they have an inviolable attachment to liberty, and say that God is to be their only Ruler and Lord. They also do not value dying any kinds of death, nor indeed do they heed the deaths of their relations and friends, nor can any such fear make them call any man lord… And it was in Gessius Florus’s time that the nation began to grow mad with this distemper, who was our procurator, and who occasioned the Jews to go wild with it by the abuse of his authority, and to make them revolt from the Romans” (See also Wars 2.8.1).

The Jewish Virtual Library adds this about Judas:

“He had put himself at the head of a band of rebels near Sepphoris and had seized control of the armory in Herod’s palace in the city. According to Josephus, he had even aspired to the throne (Ant., 17:271–2; Wars, 2:56). Though the rebels were defeated, Judah apparently succeeded in escaping (Jos., Ant., 17:289ff).”

Judas is mentioned in Acts 5 by Gamaliel when he addressed the council of the high priests and elders concerning Peter and the other apostles:

“And he said to them: ‘Men of Israel, take heed to yourselves what you intend to do regarding these men. For some time ago Theudas rose up, claiming to be somebody. A number of men, about four hundred, joined him. He was slain, and all who obeyed him were scattered and came to nothing. After this man, Judas of Galilee rose up in the days of the census, and drew away many people after him. He also perished, and all who obeyed him were dispersed…’” (Acts 5:35-37; see Antiquities 20.5.1 for the account of Theudas, the magician).

Robert Travers Herford (1860-1950), a British scholar of rabbinical literature, made an interesting comparison between Mattathias of the Maccabean revolt (167 BC) and Judas of Galilee nearly 175 years later:

“There is no certain trace of the Zealots as a party until the end of the reign of Herod; but even at the beginning of his reign there were those whose actions were of a kind precisely like the deeds of the somewhat later Zealots. Hezekiah, whom Josephus called a robber-chieftain, was put to death by Herod at the beginning of his reign. His son was that Judas of Galilee who was the real founder of the Zealot party; but Hezekiah only did much what Judas did, and the so-called robber-chieftain, though he failed, sounded the first note of the rebellion, which became the great war of A.D. 66-70.

It is no doubt true that the Zealot party took definite shape as an organised body under Judas, about the year A.D. 6, when the census was taken by of Quirinius; but their origin can be traced to an earlier date, with considerable probability. The Maccabean revolt had begun, in 167 B.C., by the sudden call of the priest Mattathias to resist the agents of the tyrant who would compel the Jews to disown their religion and disobey their God. Mattathias cried, ‘Whoso is zealous for the Torah…let him follow me’ (I Macc. ii. 27).

The word translated ‘zealous’ is (in Greek as well as in English) practically the same as the word ‘zealot.’ Moreover the Hebrew name ‘Kannaim,’ which was the name of the party as organised by Judas of Galilee, is used in a law which dates from the Maccabean times. It would seem probable that Judas, when he organised the Zealots into a party, made it his object to repeat the exploits of the first Maccabeans, by violent measures against all who were disaffected in their adherence to the Torah and ready to submit to the heathen king. The rebellion begun by Judas Maccabaeus had led to the liberation of the people from the foreign yoke and the establishment of an independent kingdom. That kingdom had only passed out of Maccabean hands when Herod acquired the throne; and the fact that every later attempt to recover it by his descendants found support amongst the people, shows that the memory of what the Maccabeans had done was still able to fire the popular mind in the time of Judas of Galilee.”

(Herford, Judaism in the New Testament Period [London: The Lindsey Press, 1928], pp. 66-67)

Less information seems to be known about Zadok, the Pharisee, who worked with Judas in heading “a large number of Zealots.”

Jacob, Simon, and Jair (sons of Judas)

Judas the Galilean had three sons: Jacob (also called James), Simon (also called Simeon), and Jair (or Jairus or Yair). While Tiberius Alexander was the Roman procurator of Judea (AD 46-48), he had Jacob and Simon crucifed because of the rebellions they led:

“…the sons of Judas of Galilee were now slain; I mean of that Judas who caused the people to revolt, when Cyrenius came to take an account of the estates of the Jews, as we have showed in a foregoing book. The names of those sons were James and Simon, whom Alexander commanded to be crucified” (Antiquities 20.5.2).

It’s difficult to find information on Jair, but (as we will see) his son, Eleazar, was a prominent leader during the Jewish-Roman War who led the final rebel holdout at Masada until AD 73.

Zealots in Jesus’ Lifetime

One of the 12 disciples whom Jesus chose was a Zealot. Luke mentions “Simon called the Zealot” when he names the disciples (Luke 6:15), and “Simon the Zealot” is again included in his list of those who stayed in an upper room after Jesus’ ascension (Acts 1:13).

Barabbas was another Zealot. He was the “notorious prisoner” (Matthew 27:16) who was released by Pilate instead of Jesus (Matthew 27:16). Barabbas and “his fellow insurrectionists” had recently “committed murder in the insurrection” (Mark 15:7) which took place in Jerusalem (Luke 23:19).

Some scholars believe that the two thieves who were crucified on either side of Jesus were also Zealots. Mark 15:27 refers to them as “two robbers,” using the same term that Josephus often used to describe the Zealots. It’s also the same term that John used to describe Barabbas: “Now Barabbas was a robber” (John 18:40).

Herford believed that Judas Iscariot was also a Zealot. He pointed out that “the headquarters of the Zealots were in Galilee,” where Jesus spent a lot of His time and where He chose His first disciples: “Of all the types of Judaism…the Zealots are the only ones with whom Jesus would have much opportunity of coming in contact” when He was in Galilee (Herford, Judaism in the New Testament Period, p. 71). Gary J. Goldberg, editor of “The Flavius Josephus Home Page,” shares a similar idea: “Judas Iscariot is thought by some to have derived his name from the Sicarii, the terrorists prior to the war” (Goldberg, Causes of War).

Martin Hengel (p. 340) says that when Jesus was arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane, He apparently asked why He was being arrested as if He were a Zealot. “Then Jesus answered and said to them, ‘Have you come out, as against a robber, with swords and clubs to take Me?’” (Mark 14:48).

Eleazar ben Ananias (AD 66)

Eleazar ben Ananias was not in the family dynasty of Hezekiah and Judas the Galilean, but he was the son of Ananias the high priest. When the Jewish-Roman War began, he was the governor of the temple, (Antiquities 20.9.3, Wars 2.17.2), the second highest position in the temple other than high priest. It’s suggested that he obtained this position in 62 AD. This position was known as “segan” (Aramaic) or “sagan” (Hebrew). According to Rabbi Hanina Segan ha-Kohanim (40-80 AD), “In case the high-priest became unfit for service, the ‘Segan’ [Deputy] should enter at once to do the service” (Talmud, Tractate Sota 42a).

Eleazar’s father, Ananius ben Nedebaios, was the high priest from roughly 46-52 AD. He’s the one who commanded Paul to be struck on the mouth during his appearance before the Sanhedrin (Acts 23:2), prompting Paul to prophesy that Ananias would also be struck (verse 3). Ananius also gave evidence against Paul to the governor Felix at Caesarea (Acts 24:1). Ananias was pro-Roman, unlike his son, Eleazar.

When Albinus was the Roman Procurator of Judea (AD 62-64), Eleazar was kidnapped by the Sicarii and was eventually let go when their demand was met:

“But now the Sicarii went into the city by night, just before the festival, which was now at hand, and took the scribe belonging to the governor of the temple, whose name was Eleazar, who was the son of Ananus [Ananias] the high priest, and bound him, and carried him away with them; after which they sent to Ananias, and said that they would send the scribe to him, if he would persuade Albinus to release ten of those prisoners which he had caught of their party; so Ananias was plainly forced to persuade Albinus, and gained his request of him. This was the beginning of greater calamities; for the robbers perpetually contrived to catch some of Ananias’s servants” (Antiquities 20.9.3).

In the book, Final Decade before the End (p. 219), Ed Stevens says that Eleazar ben Ananias led a challenge against Roman troops in May AD 66. “When the Roman Procurator Gessius Florus brought his soldiers to Jerusalem to confiscate all the gold from the Temple,” Yosippon recorded the following:

“[Eleazar b. Ananius]… being a youth and very stout of heart, saw the evil that Florus did among the people. He sounded the shofar, and a band of youths and bandits, men of war, gathered around him, and he initiated a battle, challenging Florus and the Roman troops [Sepher Yosippon, ch. 59].”

In August AD 66 Eleazar made a decision which Josephus said marked “the true beginning” of the Jewish-Roman War. He put a stop to all the sacrifices and offerings of the Gentiles, something which had never been done since the days of Moses and Aaron:

“At the same time Eleazar, the son of Ananias the high priest, a very bold youth, who was at that time governor of the temple, persuaded those that officiated in the Divine service to receive no gift or sacrifice for any foreigner. And this was the true beginning of our war with the Romans; for they rejected the sacrifice of Caesar on this account; and when many of the high priests and principal men besought them not to omit the sacrifice, which it was customary for them to offer for their princes, they would not be prevailed upon. These relied much upon their multitude, for the most flourishing part of the innovators assisted them; but they had the chief regard to Eleazar, the governor of the temple” (Wars 2.17.2).

At that time, as this quote reveals, Eleazar was considered to be the chief leader of the temple guard and those in the temple complex who wanted to revolt against Rome. Josephus also mentioned that Eleazar and his colleagues had “brought up novel rules of a strange Divine worship” (Wars 2.17.3).

He was mentioned again in Wars 2.17.5 as being among “the seditious” (the Zealots) who “had the lower city [of Jerusalem] and the temple in their power,” while “the men of power, with the high priests, as also all the part of the multitude that were desirous of peace, took courage, and seized upon the upper city [Mount Sion].” Under Eleazar, the seditious “joined to themselves many of the sicarii,” burned the palaces of Agrippa and Bernice as well as the house of Ananias the high priest, burned the contracts of creditors (“in order to gain the multitude of those who had been debtors”), drove the moderate leaders out of the upper city, and slaughtered the Roman garrison at the Fortress of Antonia (Wars 2.17.6-7).

Soon after this, Eleazar’s father, Ananius was killed by “Manahem, the son of Judas, that was called the Galilean” (Wars 2.17.8-9). Menahem “became the leader of the sedition” in September AD 66, according to Josephus, but only for about a month. “Eleazar and his party” avenged his father’s death and killed Menahem. In December AD 66, Eleazar was named as one of the 10 generals for war against Rome, and he was assigned to Idumea, a region south of Judea (Wars 2.20.4). It appears that, after this, Josephus never mentioned him again.

Eleazar ben Jair (AD 66–73)

A different Eleazar also played a key role in the Zealot cause near the beginning of the Jewish-Roman War. Eleazar ben Jair (or Jairus) was a grandson of Judas the Galilean, and part of Hezekiah’s family dynasty. Josephus mentioned him for the first time in Wars 2.17.9 as one of the people who tried to defend Menahem (his relative) after he had killed Ananias:

“A few there were of them who privately escaped to Masada, among whom was Eleazar, the son of Jairus, who was of kin to Manahem, and acted the part of a tyrant at Masada afterward.”

However, Josephus later provided information which shows that Eleazar played a key role in the Zealot cause before Menahem rose to prominence. This is what Josephus said when he introduced the topic of Masada’s overthrow in AD 73:

“This fortress was called Masada. It was one Eleazar, a potent man, and the commander of these Sicarii, that had seized upon it. He was a descendant from that Judas who had persuaded abundance of the Jews, as we have formerly related, not to submit to the taxation when Cyrenius was sent into Judea to make one” (Wars 7.8.1).

Here’s how Josephus described the Sicarii’s successful assault upon Masada in August AD 66, which resulted in the deaths of the Romans who had been stationed there. By inference, this is where Josephus first spoke of Eleazar ben Jairus:

“And at this time it was that some of those that principally excited the people to go to war made an assault upon a certain fortress called Masada. They took it by treachery, and slew the Romans that were there, and put others of their own party to keep it” (Wars 2.17.2).

Fortress of Masada, Built by Herod I (Source: National Geographic)

So when Menahem stole arms from king Herod’s armory at Masada to use in Jerusalem [Wars 2.17.8.433-434], Eleazar had already captured Masada, which was located about 60 miles southeast of Jerusalem. After trying to defend Menahem in Jerusalem in September AD 66, and fleeing to Masada when their operation failed, Eleazar apparently remained there until he led hundreds of others in a mass suicide in AD 73.

The Jewish Encyclopedia says that Eleazar succeeded Menahem “as master of Masada” and that he “took up the war of rebellion against Rome and carried it to the very end.” Masada was the final holdout in the Jewish-Roman War. Josephus said that the time came when “all the rest of the country was subdued” and “there was but one only stronghold that was still in rebellion,” i.e. Masada (Wars 7.8.1).

Eleazar built a wall around the entire fortress, and placed guards in various places (and later hastily built a second wall when the Romans were about to breach the first one). It was painful and difficult for Eleazar and his followers to obtain food and water (Wars 7.8.2), but they were determined not to surrender. However, the Roman commander, Silva, burnt down the second wall and Eleazar determined that all of them had to kill themselves rather than be captured, tortured, and killed by the Romans. His speeches to his followers are rather revealing, and can be seen in Wars 7.8.6-7, and the rather graphic details of how they committed mass suicide can be seen in Wars 7.9.1. Only a group of women, who had managed to hide themselves in an underground cavern, lived to tell the story of what happened at Masada (Wars 7.9.2).

Menahem (AD 66; grandson of Judas)

As we’ve already seen, Menahem was a relative (likely a cousin) of Eleazar ben Jairus. He was also a grandson* of Judas the Galilean and a part of Hezekiah’s family dynasty. (*Josephus referred to him as “the son of Judas,” but scholars believe he was actually Judas’ grandson.) Menahem was first mentioned by Josephus in Wars 2.17.8, where it’s said that he raided Herod’s armory at Masada, “returned in the state of a king to Jerusalem” and became the leader of the Zealot revolt. This was in late August AD 66:

“In the meantime, one Manahem, the son of Judas, that was called the Galilean, (who was a very cunning sophister, and had formerly reproached the Jews under Cyrenius, that after God they were subject to the Romans) took some of the men of note with him, and retired to Masada, where he broke open king Herod’s armory, and gave arms not only to his own people, but to other robbers also. These he made use of for a guard, and returned in the state of a king to Jerusalem; he became the leader of the sedition, and gave orders for continuing the siege.”

“The siege” was a reference to the Zealot/Sicarii assault on the Antonia Fortress, which began on the 15th of Ab (August) AD 66, resulting in the massacre of the Roman garrison that had been stationed there (Wars 2.17.7). Eleazar ben Ananias led the seditious in that attack, and they had also moved on to attack the very well-fortified palace and Agrippa’s soldiers.

Menahem, having taken over as leader, caught and killed many of Agrippa’s soldiers and set fire to their camp (Wars 2.17.8). He also overthrew “the places of strength” and killed the high priest, Ananias, and his brother. This puffed him up and made him “barbarously cruel,” so that “he thought he had no antagonists to dispute the management of affairs with him.”

Martin Hengel said that the revolution was greatly successful under Menahem and the Sicarii who followed him:

“The battle for Jerusalem was not decided until the Sicarii, who were tested in battle and were Menahem’s elite troops, had intervened. The entry of their lord into the city followed their initial successes. This was the sign that the revolution had really succeeded. The Zealots had worked for two generations towards and had now achieved their aim. Almost the entire population had joined in the Holy War against Rome” (The Zealots, p. 363).

However, Eleazar, the son of Ananias, plotted together with his party against Menahem. Part of Eleazar’s motivation was likely to avenge his father’s death, though Josephus gives other reasons (Martin Hengel also provides a good analysis on pp. 364-365 of “The Zealots”; a PDF of this book can be read or downloaded here). Eleazar and his men attacked Menahem while he was pompously worshipping in the temple, even though they knew their actions could cause the entire revolt to fail:

“They made an assault upon [Menahem] in the temple; for he went up thither to worship in a pompous manner, and adorned with royal garments, and had his followers with him in their armor. But Eleazar and his party fell violently upon him, as did also the rest of the people; and taking up stones to attack him withal, they threw them at the sophister, and thought, that if he were once ruined, the entire sedition would fall to the ground” (Wars 2.17.9).

Menahem and his men tried to resist, but they eventually fled and some were caught while others hid. Menahem was caught, taken alive and tortured, and then killed along with all of his captains. Many of the Sicarii were also caught and killed at this time, and other Sicarii fled to Masada where they were led by Eleazar ben Jairus. According to the Israeli historian, Menahem Stern,

“From this time on the Sicarii ceased to be the guiding factor in the events in Jerusalem. Nevertheless, they continued to exist and it was they who were destined to be the last to hold aloft the standard of rebellion… In addition, the considerable number of the warriors who fought under Simeon bar Giora at the time of the siege is easily explained on the assumption that many Sicarii were included in his army, since they felt themselves more in sympathy with him than with the other leaders in besieged Jerusalem. Their extreme social views bridged the gap between them and Simeon.”

Martin Hengel, author of “The Zealots” (p. 295), pointed out that Menahem’s “temporary stay as a leader in Jerusalem lasted barely four weeks,” from 15 Ab to 17 Elul in AD 66 (late August to late September). Indeed, Menahem’s quick rise to prominence and his death are recorded in just two consecutive small sections in Wars of the Jews (Wars 2.17.8-9). I believe that Menahem was the seventh king who had “not yet come” when John wrote Revelation, and who would only “continue a short time” (Revelation 17:10).

Seven Kings of Revelation 17:10 (Family Dynasty of “Hezekiah the Zealot”)

|

| “There are also seven kings. Five have fallen… |

1. Hezekiah (47 BC) |

| |

2. Judas of Galilee (led rebellion from AD 6-8) |

| |

3. Jacob (son of Judas; crucified around AD 47) |

| |

4. Simon (son of Judas; crucified around AD 47) |

| |

5. Jair (son of Judas; father of Eleazar) |

| …one is… |

6. Eleazar ben Jair (rebel leader from AD 66-73) |

| …and the other has not yet come. And when he comes, he must continue a short time” (Rev. 17:10). |

7. Menahem (rebel leader for only a month in AD 66) |

Martin Hengel said that it was evident Menahem “had both special authority and a position of power.” He added:

“He was probably not only the leader of one of the many ‘robber bands’ that were in control of the open country, but also the head of the Zealot movement in the whole of the country. His authority was based on his descent from the founder of the sect, Judas, on his own military power, which he had increased by his successful attack against Masada, and, last but not least, on his personal experience in battle and his own forceful personality” (The Zealots, p. 362).

Numerous sources say that Menahem was a Messiah figure, and even that he claimed to be the Messiah. Martin Hengel points out that, in the rabbinic Haggadah, Menahem was regarded as “the Messiah” (The Zealots, p. 295). This source also relates a legend in which a peasant heard Menahem’s mother say, “His omen is disastrous, because the Temple was destroyed on the day that he was born.” The peasant then answered, “We believe that, just as it (the Temple) was destroyed because of him, so too will it be rebuilt because of him.” Hengel interprets this legend as meaning that, to the Zealots who followed Menahem, the death of such a Messiah-figure in the temple was like sealing the doom of the temple itself.

According to the Dutch historian, Jona Lendering (at Livius),

“There is no need to doubt whether Menahem claimed to be the Messiah. He was a warrior, entered Jerusalem dressed as a king, quarreled with the high priest (who may have entertained some doubts about Menahem’s claim), and worshipped God in the Temple. We can be positive that Menahem wanted to be the sole ruler of a restored Israel.”

Kaufmann Kohler, Ph.D, a Rabbi and theologian, adds:

Rabbinical tradition alludes to Menahem’s Messiahship when stating that the Messiah’s name is Menahem the son of Hezekiah (Sanh. 98b); and according to Geiger (“Zeitschrift,” vii. 176-178), he is the one who went up with eighty couples of disciples of the Law equipped with golden armor and crying out: “Write upon the horn of the ox, ‘Ye [yielding Pharisees] have no share in the God of Israel!'” (Yer. Ḥag. ii. 77b).

In the immediate aftermath of Menahem’s death, the remaining Zealots “hoped to prosecute [the war] with less danger, now they had slain Menahem,” and the common people “earnestly desired” that they would stop attacking the Roman soldiers. Eleazar ben Ananias and his men made oaths to the soldiers that they would be spared, but it was a trick. After the soldiers laid down their swords and shields, the Zealots “attacked them after a violent manner, and encompassed them around, and slew them” (Wars 2.17.10).

Josephus adds that “men made public lamentation” when they saw this, and “the city was filled with sadness, and every one of the moderate men in it were under great disturbance.” At this time tragedies also came upon the Jews in Caesarea, Syria, Alexandria, and other places as cities and regions rose up against them. Soon, Cestius Gallus swept through Galilee in partnership with Agrippa and with thousands of soldiers, planning to capture Jerusalem and put down the rebellion. This plan was a terrible failure for Cestius Gallus, though, as we will see in the next post.

Was Menahem the wounded head of Revelation 13:3, 12? This question will be discussed at the end of this post.

Eleazar ben Simon (AD 66-70)

Eleazar ben Simon came from a priestly family (Wars 4.4.1.225), and was not part of the family dynasty of Hezekiah. He was the nephew of Simon Bar Giora (Wars 6.4.1), who will be discussed below. Eleazar was first introduced by Josephus in Wars 2.20.3 as a war hero in the victory over Cestius Gallus in November AD 66. According to Josephus, he “had gotten into his possession the prey they had taken from the Romans, and the money they had taken from Cestius, together with a great part of the public treasures.”

Soon after this victory, the rebels appointed 10 “generals for the war” (Wars 2.20.3-4). Josephus speaks of Eleazar ben Simon as a natural choice for one of those positions due to his bravery and success in the battle against Cestius Gallus. Instead he was kept out of that office because of his terrible temper and the extreme loyalty of his followers, but he managed to become the main leader of the Zealots anyway:

“They did not ordain Eleazar the son of Simon to that office… because they saw he was of a tyrannical temper; and that his followers were, in their behavior, like guards about him. However, the want they were in of Eleazar’s money, and the tricks by him, brought all so about, that the people were circumvented, and submitted themselves to his authority in all public affairs” (Wars 2.20.3).

This was still true almost 1.5 years later, in early AD 68. Josephus said that among the Zealot leaders, he was “the most plausible man, both in considering what was fit to be done, and in the execution of what he had determined upon” (Wars 4.4.1). John Levi of Gischala, who will be discussed next, joined forces with Eleazar ben Simon at this time, and, after killing Ananus ben Ananus and other high priests in February-March AD 68 AD, together they seized control of the entire city of Jerusalem (Wars 4.4.1 – 4.6.3).

Eleazar made the temple his headquarters for nearly 3.5 years, from late AD 66 until he was defeated by John Levi’s forces in mid-April AD 70. Josephus said that it was “Eleazar, the son of Simon, who made the first separation of the zealots from the people, and made them retire into the temple” (Wars 5.1.2). Around December AD 67, Eleazar and the other Zealots made the sanctuary of the temple “a shop of tyranny” by casting lots to select a fake high priest named Phannias. He was chosen against his will from a village in the countryside, fitted with “a counterfeit face” and the sacred garments, and “upon every occasion [they] instructed him what he was to do” (Wars 4.3.6-8).

In the spring of AD 69, Eleazar “was desirous of gaining the entire power and dominion to himself” and he “revolted from John [Levi].” He and his followers “seized upon the inner court of the temple” and made use of the sacred things in there (Wars 5.1.2). At this time, he led one of three Zealot factions, with the other factions being led by John Levi and Simon Bar Giora (Wars 5.1.1, 4; Revelation 16:19).

Source: Mark Mountjoy, New Testament Open University (June 9, 2015)

Eleazar ben Simon was tricked and defeated by John Levi’s forces in mid-April AD 70, just as the Roman general Titus began his siege. This happened at the Feast of Unleavened Bread. Eleazar opened the gates to the inner court of the temple

“and admitted such of the people as were desirous to worship God into it. But John made use of this festival as a cloak for his treacherous designs, and armed the most inconsiderable of his own party, the greater part of whom were not purified, with weapons concealed under their garments, and sent them with great zeal into the temple, in order to seize upon it; which armed men, when they were gotten in, threw their garments away, and presently appeared in their armor… These followers of John also did now seize upon this inner temple, and upon all the warlike engines therein, and then ventured to oppose Simon. And thus that sedition, which had been divided into three factions, was now reduced to two” (Wars 5.3.1).

After this treachery, Josephus records that Eleazar ben Simon’s 2,400 men stopped opposing John Levi and joined forces with him, but Eleazar remained as their commander:

“John, who had siezed upon the temple, had six thousand armed men, under twenty commanders; the zealots also that had come to him, and left off their opposition, were two thousand four hundred, and had the same commander that they had formerly, Eleazar, together with Simon the son of Arinus” (Wars 5.6.1.250).

Eleazar ben Simon is mentioned one last time in Wars of the Jews. Josephus described the state of affairs as of the 8th of Av (late July or early August) in AD 70 when two of the Roman legions completed their banks. Josephus mentioned that Eleazar was still involved in the fighting at this time: “Of the seditious, those that had fought bravely in the former battles did the like now, as besides them did Eleazar, the brother’s son of Simon the tyrant” (Wars 6.4.1).

Eleazar’s death is not mentioned in Wars of the Jews, but there is also no mention of his survival or capture (unlike the other two main Zealot leaders, John Levi and Simon Bar Giora). Various online sources seem to be unanimous that Eleazar died in AD 70 around the time when the temple was burned and destroyed.

John Levi of Gischala (AD 66-70)

John Levi was from Gischala in Galilee, and was not part of Hezekiah’s family dynasty. Josephus wrote extensively about him in his book, “The Life of Flavius Josephus.” John was not a Zealot from the beginning. At one point, when the people of Gischala wanted to revolt against the Romans, John tried to restrain them and he urged them to “keep their allegiance to [the Romans]. However, Gischala was then attacked, set on fire, and demolished by non-Jews from neighboring regions. At that point, John became enraged, “armed all his men,” joined the battle, but also rebuilt Gischala “after a better manner than before, and fortified it with walls for its future security” (Life 10.43-45).

In Wars of the Jews, John was first mentioned in Wars 2.21.1 as “a treacherous person,” a “hypocritical pretender to humanity,” and as one who “spared not the shedding of blood” and “had a peculiar knack of thieving.” According to Josephus, John gathered together a band of four hundred men mostly from Tyre, who were greatly skilled “in martial affairs,” and they “laid waste all Galilee.” These things took place while Josephus was “engaged in the administration of the affairs of Galilee,” beginning around December AD 66, since he had been appointed as a general for the war (Wars 2.20.3-4).

Josephus said that John Levi became wealthy through an oil scheme, and he also wanted to “overthrow Josephus” and “obtain the government of Galilee” for himself. He had a number of “robbers” under his command. He spread a rumor that Josephus was planning to give Galilee to the Romans and engaged in other plots against him (Wars 2.21.2), including a murder attempt that Josephus barely escaped (Wars. 2.21.6).

The Encyclopedia Judaica summarizes John’s last unsuccessful plot against Josephus (Wars 2.21.6-8) and his failed attempt almost a year later to save Gischala from the Romans (Wars 4.2.1-5):

“John dispatched a delegation to Jerusalem, demanding that Josephus be dismissed from his position for failing to fulfill his tasks loyally. This request was acceded to, according to Josephus, as a result of John’s bribery and exploitation of his friendship with Simeon b. Gamaliel. Emissaries were sent to dismiss Josephus from his command and advise the citizens of Galilee to support John. Josephus ignored all this and went so far as to threaten John’s supporters…

John’s efforts to organize Galilee for war were unsuccessful and, with the exception of his native city, the whole province fell to the Romans. In the winter of 67, when Titus was at the gates of Giscala and offered terms of surrender, John seized on the intervening Sabbath as a pretext for delaying negotiations and escaped to Jerusalem.

“John of Giscala.” Encyclopaedia Judaica. Encyclopedia.com. 3 Mar. 2017.

John escaped to Jerusalem in November AD 67, a year and three months after the Jewish-Roman War began. He and his followers immediately told tall tales about their fight with the Romans at Gischala:

Now upon John’s entry into Jerusalem, the whole body of the people were in an uproar, and ten thousand of them crowded about every one of the fugitives that were come to them, and inquired of them what miseries had happened abroad, when their breath was so short, and hot, and quick, that of itself it declared the great distress they were in; yet did they talk big under their misfortunes, and pretended to say that they had not fled away from the Romans, but came thither in order to fight them with less hazard; for that it would be an unreasonable and a fruitless thing for them to expose themselves to desperate hazards about Gischala, and such weak cities, whereas they ought to lay up their weapons and their zeal, and reserve it for their metropolis. But when they related to them the taking of Gischala, and their decent departure, as they pretended, from that place, many of the people understood it to be no better than a flight; and especially when the people were told of those that were made captives, they were in great confusion, and guessed those things to be plain indications that they should be taken also. But for John, he was very little concerned for those whom he had left behind him, but went about among all the people, and persuaded them to go to war, by the hopes he gave them. He affirmed that the affairs of the Romans were in a weak condition, and extolled his own power. He also jested upon the ignorance of the unskillful, as if those Romans, although they should take to themselves wings, could never fly over the wall of Jerusalem, who found such great difficulties in taking the villages of Galilee, and had broken their engines of war against their walls.

These harangues of John’s corrupted a great part of the young men, and puffed them up for the war; but as to the more prudent part, and those in years, there was not a man of them but foresaw what was coming, and made lamentation on that account, as if the city was already undone; and in this confusion were the people…” (Wars 4.3.1-2).

Soon after this, Phannias was chosen by lots and installed as a fake high priest and a puppet of the Zealots (Wars 4.3.6-8). Ananus ben Ananus and the other priests shed tears as they watched this mockery take place. Ananus gathered a multitude of the people and gave a speech rebuking them for allowing the Zealots to fill the temple with abominations, plunder houses, shed the blood of innocent people, etc. Ananus said that nothing they could undergo from the Romans would be harder to bear than what the Zealots had already brought upon them. He urged them to rise up together against the Zealots, and said that he was willing to die leading them in that effort (Wars 4.3.10).

Ananus and his followers attacked the Zealots and tried to trap many of them in the temple complex (Wars 4.3.12). John Levi pretended to share their opinion and “at a distance was the adviser in these actions.” He consulted with Ananus and other moderate leaders every day and “cultivated the greatest friendship possible with Ananus, but “he divulged their secrets to the zealots.” His deceit became so great that “Ananus and his party believed his oath” to them, and “sent him as their ambassador into the temple to the zealots, with proposals of accommodation” (Wars 4.3.13).

John betrayed Ananus and falsely claimed that he had invited the Roman general, Vespasian, to conquer Jerusalem (Wars 4.3.14). In response, the Zealot leaders, Eleazar ben Simon and Zacharias ben Phalek, requested help from the Idumeans, who lived south of Judea, and the Idumeans quickly prepared an army of 20,000 directed by four commanders (Wars 4.4.2). The day they arrived (in late February AD 68) they were prevented from entering the city, but the next day they managed to hunt down and kill Ananus and Jesus (Wars 4.5.2). Their deaths marked a significant turning point for Jerusalem, according to Josephus:

“I should not mistake if I said that the death of Ananus was the beginning of the destruction of the city, and that from this very day may be dated the overthrow of her wall, and the ruin of her affairs, whereon they saw their high priest, and the procurer of their preservation, slain in the midst of their city… to say all in a word, if Ananus had survived they had certainly compounded matters… And the Jews had then put abundance of delays in the way of the Romans, if they had had such a general as he was” (Wars 4.5.2).

After their deaths, the Zealots and the Idumeans “fell upon the people as upon a flock of profane animals, and cut their throats.” Others endured “terrible torments” before finally meeting their deaths. At least 12,000 died in that massacre (Wars 4.5.3). Then one of the Zealots told the Idumeans that they had been tricked, and that Ananus and the high priests never did plot to betray Jerusalem to the Romans. So the Idumeans regretted their actions, saw “the horrid barbarity of [the Zealots who] had invited them,” and left Jerusalem (Wars 4.5.5). The Zealots, no longer hindered by the high priests or even the Idumeans, then increased their wickedness (Wars 4.6.1). John Levi began to tyrannize, didn’t want anyone to be his equal, and he gradually put together “a party of the most wicked” of all the Zealots and started his own faction (Wars 4.7.1).

By the time that there were “three treacherous factions in the city” (Wars 5.1.4), John had the second largest contingent of Zealot fighters (Wars 5.6.1):

[1] Simon Bar Giora: 10,000 men and 50 commanders; 5000 Idumeans and eight commanders

[2] John Levi: 6,000 men and 20 commanders

[3] Eleazar ben Simon: 2,400 men

As we’ve already seen, John’s forces tricked and killed Eleazar ben Simon in mid-April AD 70 (Wars 5.3.1), just as Titus was laying siege to Jerusalem. He then had access to the inner court of the temple and didn’t hesitate to commit sacrilegious acts during the siege (fulfilling Revelation 6:6):

“But as for John, when he could no longer plunder the people, he betook himself to sacrilege, and melted down many of the sacred utensils, which had been given to the temple; as also many of those vessels which were necessary for such as ministered about holy things, the caldrons, the dishes, and the tables; nay, he did not abstain from those pouring vessels that were sent them by Augustus and his wife; for the Roman emperors did ever both honor and adorn this temple; whereas this man, who was a Jew, seized upon what were the donations of foreigners, and said to those that were with him, that it was proper for them to use Divine things, while they were fighting for the Divinity, without fear, and that such whose warfare is for the temple should live of the temple; on which account he emptied the vessels of that sacred wine and oil, which the priests kept to be poured on the burnt-offerings, and which lay in the inner court of the temple, and distributed it among the multitude, who, in their anointing themselves and drinking, used [each of them] above an hin of them” (Wars 5.13.6).

Toward the end of the siege, as Jerusalem was on fire, John joined “the tyrants and that crew of robbers” whose last hope was to hide “in the caves and caverns underground” (Wars 6.7.3; Revelation 6:15-17). Due to great hunger, he surrendered to the Romans, was taken captive, and was “condemned to perpetual imprisonment” (Wars 6.9.4). Among the captives who were carried off to Italy for a triumphal parade, John was considered to be their second leader, after Simon Bar Giora, “the general of the enemy” (Wars 7.5.3, Wars 7.5.6).

Simon Bar Giora (AD 66-70)

Simon Bar Giora was not a member of Hezekiah’s family dynasty, but it seems that he fit in with them better than the other Zealot leaders around the time of the war who were not part of this dynasty. Simon was the uncle of Eleazar ben Simon. In Wars 6.4.1 Josephus refers to Eleazar ben Simon as “the brother’s son of Simon the tyrant.” He was originally from Gerasa (Wars 4.9.3). Martin Hengel remarks:

“As his name indicates, Simon Bar Giora was the son of a proselyte. He came originally not from the Jewish motherland, but from Gerasa in the Hellenistic Decapolis. This was a town which had dealt with its Jewish inhabitants not by killing them, but by simply expelling them from its territory. We do not know when Simon left his home town” (The Zealots, p. 374).

Cecil Roth, a Jewish historian from Britain (Oxford), said this in a 1960 article about Simon’s name:

“The form of the name “bar Giora” derives not from Josephus but from Tacitus, who in his brief account of the war refers to him under this name, although confusing him with his rival John of Gischala (‘Ioannes, quern et Bargioram vocabant’) . Josephus speaks of him always as “son of Giora” or the like. ‘Bar Giora’ is of course the form in the Aramaic language, already at this time current in Palestine. Giora is never met with as a proper name, but in Aramaic it means ‘proselyte,’ equivalent to the Hebrew Ger.”

Simon Bar Giora was first mentioned by Josephus in Wars 2.19.2, where he was credited with ambushing the rear of Cestius Gallus’ army in November AD 66 as they retreated from a surprise attack by the Jews: “Simon, the son of Giora, fell upon the backs of the Romans, as they were ascending up Bethoron, and put the hindmost of the army into disorder, and carried off many of the beasts that carded the weapons of war, and led Shem into the city.”

Then in Wars 2.22.2 Josephus says that Simon Bar Giora ravaged the Accrabene Toparchy (at the border of Judea and Samaria), harassing the houses of rich men, tormenting their bodies, and “affecting tyranny in his government” (early AD 67). When an army was sent against him by Ananus ben Ananus (see Wars 4.9.3), he joined “the robbers” (the Sicarii) at Masada “and plundered the country of Idumea with them, till both Ananus and his other adversaries were slain.”

Simon wasn’t spoken of in any detail again until Wars 4.9.3 (early AD 69), with one small exception. In the spring of AD 68, the Idumeans liberated about 2000 people from the prisons in Jerusalem before themselves leaving the city. Interestingly, those prisoners “fled away immediately to Simon” (Wars 4.6.1). This indicates the extent of his fame and influence even when he wasn’t in Jerusalem.

Josephus says that when Simon first came to Masada, the Sicarii were suspicious of him, but they began to trust him when they saw that “his manner so well agreed with theirs.” So “he went out with them, and ravaged and destroyed the country with them about Masada.” Simon was “fond of greatness.”

When he heard the report that Ananus had been killed (late February AD 68), he went into the mountainous part of Judea and “proclaimed liberty to those in slavery, and a reward to those already free, and got together a set of wicked men from all quarters” (Wars 4.9.3). The Jewish historian, Cecil Roth, said that it was as if Simon tried to apply Isaiah 61:1-2 to himself the way that Jesus did in Luke 4:16-21, except that for Simon “the Day of Vengeance for the Lord” had already arrived. In any case, it’s interesting that Simon, located at Masada, cast off restraint upon the death of Ananus just like the Zealots in Jerusalem did (Wars 4.6.1).

Simon, with “a strong body of men,” overran villages and became a threat “to the cities.” He had men of power, slaves and robbers, and “a great many of the populace” who “were obedient to him as their king.” According to Josephus, it was no secret that he was “making preparations for the assault of Jerusalem” (Wars 4.9.4). The Zealots were afraid that he would attack them and so they attacked him first, but unsuccessfully. Simon had 20,000 armed men. Before heading to Jerusalem, he “resolved first to subdue Idumea” (Wars 4.9.5).

When Simon marched into Idumea, he began by capturing the city of Hebron. Then he made “progress over all Idumea, and did not only ravage the cities and villages, but laid waste the whole country.” At that point, he had 40,000 followers besides his 20,000 armed men. As a result, “Idumea was greatly depopulated; and as one may see all the woods behind despoiled of their leaves by locusts, after they have been there, so was there nothing left behind Simon’s army but a desert” (Wars 4.9.7).

The Zealots made the mistake of kidnapping his wife, thinking that he would lay down his arms, but Simon “vented his spleen upon all persons that he met with,” shed a lot of blood, and got his wife back (Wars 4.9.8-10). Then he returned to Idumea and “driving the nation all before him from all quarters, he compelled a great number of them to retire to Jerusalem; he followed them himself also to the city” (Wars 4.9.10).

Meanwhile, in Jerusalem there was an uprising against John Levi “out of their envy at his power and hatred of his cruelty.” So, surprisingly, “in order to overthrow John, they determined to admit Simon, and earnestly to desire the introduction of a second tyrant into the city.” Simon, “in an arrogant manner, granted them his lordly protection… The people also made joyful acclamations to him, as their savior and their preserver” (Wars 4.9.11). According to Josephus, Simon “got possession of Jerusalem” around April AD 69 (Wars 4.9.12). Before long, he had “in his power the upper city, and a great part of the lower” (Wars 5.1.3). As we’ve already seen, he had more commanders and armed men with him than John Levi and Eleazar ben Simon had combined (Wars 5.6.1).

In the book, “Simon Son of Man,” published in 1917, the authors (John I. Riegel and John H. Jordan) pointed out the great influence that Simon Bar Giora had during the Jewish-Roman War (AD 66-73), even from its beginning. Although Josephus says that Simon only took control of Jerusalem in AD 69, it was his name that was printed on most of the coins issued by the Zealots beginning in 66 AD (pp. 256 – 259):

The study of Jewish numismatics throws much light upon the personality of Simon Bar Gi’ora and his relations with Eleazar and John during the siege of the Holy City… Of the 36 coins of the period of the great revolt illustrated in Madden’s History of Jewish Coinage, 29 bear the name of Simon. In so great a veneration was he held by his compatriots, even in their defeat, that during the reigns of Titus, Domitian, Trajan and Hadrian his fellow countrymen continued to strike coins bearing his emblems and his venerated name…

The prevailing form is the figure of a seven-branched date tree, with the name ‘Simon’ struck on the obverse, and a three-bunch cluster of grapes, or a similarly shaped tripartite vine leaf on the reverse, with the words ‘First’, ‘Second’ or ‘Third Year of the Deliverance of Israel.’ According to Josephus, Simon Bar Gi’ora did not enter Jerusalem until the third year of the war, yet we possess coins issued by Simon which bear the inscriptions, ‘Second,’ and even ‘First year of the Deliverance of Israel’…

Josephus declares there was a bitter enmity existing between Simon Bar Gi’ora, Eleazar Son of Simon, and John, the three princes of the Jews during the siege. Yet, we have one silver coin bearing the name of Eleazar on the obverse and that of Simon on the reverse. This can only prove that Simon and Eleazar acted conjointly even to the extent of minting coins in common…

The coining of money is always the prerogative of the sovereign power in a state. The extant coinage issued in Jerusalem during the siege, struck from almost identical dies, shows how the sovereign power within was divided and mutually recognized. Of course, the number of extant coins bearing the name of Simon far outnumber those of his coadjutors in power, Eleazar and John, and in proportion as they do so they show the relative influence of each on the government of the state and how the sovereign power eventually became vested in the greatest of the three.”

Source: Simon Son of Man, Riegel and Jordan, p. 257

As the Roman siege began, John Levi was afraid of Simon Bar Giora (Wars 5.6.3). Sometime later, though, the two factions led by Simon and John decided to lay aside their differences and work together (with the result being that several times they “became too hard for the Romans” and Titus was even nearly killed):

“Both sorts, seeing the common danger they were in, contrived to make a like defense. So those of different factions cried out one to another, that they acted entirely as in concert with their enemies; whereas they ought however, notwithstanding God did not grant them a lasting concord, in their present circumstances, to lay aside their enmities one against another, and to unite together against the Romans. Accordingly, Simon gave those that came from the temple leave, by proclamation, to go upon the wall; John also himself, though he could not believe Simon was in earnest, gave them the same leave. So on both sides they laid aside their hatred and their peculiar quarrels, and formed themselves into one body” (Wars 5.6.4).

Simon and John worked together in the most sinister way, falsely accusing people of plotting against them, attempting to betray Jerusalem to the Romans, or attempting to flee to the Romans. Josephus says that they passed these victims back and forth between each other:

“For the men that were in dignity, and withal were rich, they were carried before the tyrants themselves; some of whom were falsely accused of laying treacherous plots, and so were destroyed; others of them were charged with designs of betraying the city to the Romans; but the readiest way of all was this, to suborn [hire] somebody to affirm that they were resolved to desert to the enemy. And he who was utterly despoiled of what he had by Simon was sent back again to John, as of those who had been already plundered by Jotre, Simon got what remained; insomuch that they drank the blood of the populace to one another, and divided the dead bodies of the poor creatures between them; so that although, on account of their ambition after dominion, they contended with each other, yet did they very well agree in their wicked practices” (Wars 5.10.4).

Yet the Jews had the highest regard for, and fear of, Simon. They were also very ready to take their own lives, if he would have given such a command: “Above all, they had a great veneration and dread of Simon; and to that degree was he regarded by every one of those that were under him, that at his command they were very ready to kill themselves with their own hands” (Wars 5.7.3).

Toward the end of the Roman siege of Jerusalem, John Levi and many others had already been captured by the Romans, but Simon was still underground and hoping to escape. Josephus recorded his bizarre behavior when he finally emerged dressed like a king, hoping to trick the Romans, but was captured and kept for the eventual celebration in Rome. Interestingly, he chose to come up out of the ground exactly where the temple had been:

“This Simon, during the siege of Jerusalem, was in the upper city; but when the Roman army was gotten within the walls, and were laying the city waste, he then took the most faithful of his friends with him, and among them some that were stone-cutters, with those iron tools which belonged to their occupation, and as great a quantity of provisions as would suffice them for a long time, and let himself and all them down into a certain subterraneous cavern that was not visible above ground. Now, so far as had been digged of old, they went onward along it without disturbance; but where they met with solid earth, they dug a mine underground, and this in hopes that they should be able to proceed so far as to rise from underground in a safe place, and by that means escape. But when they came to make the experiment, they were disappointed of their hope; for the miners could make but small progress, and that with difficulty also; insomuch that their provisions, though they distributed them by measure, began to fail them.

And now Simon, thinking he might be able to astonish and elude the Romans, put on a white frock, and buttoned upon him a purple cloak, and appeared out of the ground in the place where the temple had formerly been. At the first, indeed, those that saw him were greatly astonished, and stood still where they were; but afterward they came nearer to him, and asked him who he was. Now Simon would not tell them, but bid them call for their captain; and when they ran to call him, Terentius Rufus who was left to command the army there, came to Simon, and learned of him the whole truth, and kept him in bonds, and let Caesar know that he was taken. Thus did God bring this man to be punished for what bitter and savage tyranny he had exercised against his countrymen by those who were his worst enemies; and this while he was not subdued by violence, but voluntarily delivered himself up to them to be punished, and that on the very same account that he had laid false accusations against many Jews, as if they were falling away to the Romans, and had barbarously slain them for wicked actions do not escape the Divine anger, nor is justice too weak to punish offenders, but in time overtakes those that transgress its laws, and inflicts its punishments upon the wicked in a manner, so much more severe, as they expected to escape it on account of their not being punished immediately. Simon was made sensible of this by falling under the indignation of the Romans. This rise of his out of the ground did also occasion the discovery of a great number of others of the seditious at that time, who had hidden themselves under ground. But for Simon, he was brought to Caesar in bonds, when he was come back to that Cesarea which was on the seaside, who gave orders that he should be kept against that triumph which he was to celebrate at Rome upon this occasion” (Wars 7.2.2).

Among the leaders of the captives taken from Jerusalem, Simon was listed first by Josephus (Wars 7.5.3). The Israeli historian Menahem Stern pointed out that the Roman historian, Tacitus, also listed him first:

“Both Simeon and John are mentioned side by side with Eleazar b. Simeon as the commanders in Jerusalem, not only by Josephus but by the Roman historian Tacitus, who enumerates Simeon first and Eleazar last. Titus also regarded Simeon bar Giora as the leading commander and it was he who was chosen by the Romans to exemplify an enemy commander and lead the triumphal procession in Rome.”

“Judaea Capta” coin from AD 71 (Source)

This triumphal procession is described in Wars 7.5.1-7. Simon was called “the general of the enemy” and his execution was in “the last part of this pompous show…at the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus.” A rope was put around his head and he was tormented as he was dragged along. All the people shouted for joy when it was announced that he had been killed (Wars 7.5.6). A Jewish Encyclopedia article written in 1906 by Richard Gottheil (Professor of Semitic Languages, Columbia University) and Samuel Krauss (Professor in Budapest, Hungary) states that he was hurled to his death from the Tarpeian Rock. However, Cecil Roth, the Oxford Jewish historian, stated in a 1960 article that Simon was “was dragged to the Mamertine Prison, where he was strangled in the subterranean chamber.”

A 2007 article in Encyclopaedia Judaica says the following about Simon and his likely “king messiah” role:

“From extant information it would appear that Simeon b. Giora was the leader of a clear eschatological trend in the movement of rebellion against Rome, and possibly filled the role of ‘king messiah’ within the complex of eschatological beliefs held by his followers. His exceptional bravery and daring, mentioned by Josephus, undoubtedly attracted many to him, and won him preeminence among the rebel leaders. In contrast to the bitter hostility that existed between him and John of Giscala, there was a measure of understanding between him and the Sicarii at Masada.”

“Bar Giora, Simeon.” Encyclopaedia Judaica. Encyclopedia.com. 3 Mar. 2017.

Martin Hengel, in The Zealots (pp. 290-298), agreed that Simon “made claims to Messianic dignity” (p. 297). According to Hengel, [1] Judas of Galilee [2] Menahem, and [3] Simon Bar Giora were all Messianic pretenders. He cited close similarities between Menahem and Simon Bar Giora in that they both marched into Jerusalem like kings, were both regarded by their followers as kings, and both dressed in royal garments when they were captured by their enemies.

Wounded Head

After this long overview of the Zealot movement and its various leaders, we come back to the question: “Who was the wounded head of Revelation 13:3?” Here, again, is what this verse states:

“And I saw one of his heads as if it had been mortally wounded, and his deadly wound was healed. And all the world marveled and followed the beast.”

Several translations, by the way, including Young’s Literal Translation, say “all the earth marveled…” rather than “all the world marveled…” The Greek word for “the earth” (“ge”) can be translated as “the land.” That is, it was the land of Israel that marveled after the beast on account of its deadly wound being healed.

Almost 120 years after the uprising of Hezekiah, and 60 years after the uprising of Judas of Galilee, another head of the Zealot movement was crushed, which jeopardized the plans of the movement and destroyed its unity and momentum. That head was Menahem, who achieved victories at Masada, came into Jerusalem as a king, and became the leader of the Zealots, only to be killed about one month later. Martin Hengel says this about the ramifications of Menahem’s sudden death, which was especially untimely because it took place only about a month after the Jewish-Roman War officially began:

“This whole sequence of events led to a division in the ranks of the Zealot movement precisely at the moment when a consolidation of all its forces under a single leadership was required. It is probable that Menahem, the son of Judas, the founder of the sect, was the only man possessing the necessary authority and experience to organize a lasting resistance to the Romans based on the Zealot movement throughout the whole country…

Menahem’s most faithful followers and especially the tribe of the Galilean Judas withdrew to Masada and took no further part in the subsequent course of the war… These men believed that the Temple had been desecrated by this bloody act [Menahem’s murder] and was therefore doomed to destruction. They remained faithful to their earlier views, however, and continued to follow Eleazar b. Ari (Jair), a grandson of Judas, as their leader until their mass suicide…in April 73 A.D. The groups of Zealots in the various parts of the territories settled by the Jews lost their common leader and therefore the bond that held them together. They consequently operated without any sensible plan and were deeply distrustful of the authorities in Jerusalem…